Pragmatic Solutions for Breaking the Bias

In Australia today, you would be hard-pressed to find a person who believes that offering equal opportunities to women is the wrong thing to do. It is commonly agreed that women should not be educated differently, should not be paid less than men for the same role, and should not be held back from promotional opportunities because of their gender.

These views are shared because, for the most part, we believe in a meritocracy; the idea that anyone with the right skills and hard work can achieve their aspirations.

With these inspiring shared values in mind, Australian employers are well-positioned to address the final hurdle holding the gender gap in place: breaking the bias.

The current state of gender equality

While in recent years, many companies have become more active in their efforts to address gender diversity, women remain underrepresented at every stage of the career pipeline in Australia. Data from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency shows that even though women make up about 50% workforce, they account for just 28% of Directors, 18% of CEO’s and 14% of board chairs.

The business case for diversity is stronger than ever before. Numerous studies have demonstrated the link between women in leadership and organisational performance. Revealing that the greater the female representation in executive and senior leadership roles, the better the organisation financially performs.

With a strong business case, and overt intentions to provide equal opportunity, why do we still have so few women in senior leadership positions? The current landscape reveals the power of our biases.

The function of implicit biases

Our brains are processing 44 million of pieces of information each second, and in order to make sense of this, it looks for patterns and applies filters to simplify this load of information. This is all happening without us consciously knowing, hence the term unconscious bias. Whether we like it or not, by default of our evolution, we all hold unconscious biases. Knowing how these shortcuts can lead to biased thinking empowers us to recognise and manage the way they are holding the ‘glass ceiling’ in place.

Stereotypes are the most widely understood forms of bias: that is, a shortcut our brain uses to predict knowledge about a group of people. We all know stereotyping is harmful and we do our best to check that we’re not relying on stereotypes to make decisions about who we’d like to spend time with, who we trust, and what we expect from people.

Research has shown that many of these biases are formed early in childhood through both explicit and implicit messages. This can include role modelling, educational institutions, television and media, and even the toys that are gendered and marketed to boys and girls. For this reason, it is possible to hold strong values around gender equality and still be operating with some unconscious bias.

There are a few types of unconscious biases that are especially relevant to holding in place gender bias in the workplace.

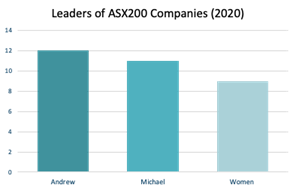

Similarity bias describes how people are more likely to show favourable behaviours to those who are like them, or who belong to the same social group as they do. This can spill over into favouring those with the same gender, or even the same name! There are currently more men named Andrew or Michael leading ASX200 companies than there are women. It’s natural to like people who are like ourselves, but unmanaged similarity bias’ can undermine the objectivity of recruitment and selection processes.

Adapted from Gender Equality at Work (Liveris, 2020)

Gender-role congruency bias occurs when stereotypes about roles unknowingly inform our judgements about a person’s ‘fit’ with the role. This happens when – for instance – the qualities associated with being a ‘woman’ (e.g., supportive), and the qualities associated with the role ‘executive’ (e.g. directive) – are inconsistent. With this incongruency, we might not see an individual woman as ‘having leadership qualities’ as clearly as we would a man who is also seen as directive.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out, favour and use information that confirms our existing assumptions and beliefs, filtering out any information that disconfirms an existing idea. This bias reinforces the two above as we find information that confirms our assumptions, leading to flawed decision making.

What can we do?

Unconscious biases are a fact of life, but they can be overcome with awareness and thoughtful action to help reduce and minimise their impact.

1. Build awareness

On an individual level, understanding that we all have biases is the first step to reducing the hold they have over us. Take, for example, the advances we’ve made from increasing our collective knowledge about the harms of stereotyping. By increasing our awareness of the brains tendency to rely on its established models and stereotypes, we’re able to catch and curb ourselves from making judgements based solely on a stereotype.

At a group and organisational level, there remains some debate about the impact implicit bias training has on changing behaviour. Some argue that the very nature of implicit bias being unconscious, means it can’t be ‘trained out’ of our people. However, without this first step, key decision-makers may be inclined to downplay the presence of gender bias. We must first raise awareness before asking for a commitment to following the systems and practices in place to mitigate the impacts of bias.

2. Systemic and structural changes

The role of affirmative action, in the way of diversity targets, has been an increasing focus of organisations working to improve gender balance in senior positions. While these targets are a useful tool, quotas alone do not automatically guarantee better outcomes. Thoughtful and deliberate actions need to follow to ensure their benefits are enduring and manage the potential harm that can follow the beneficiaries of these programs.

– Amanda Vanstone, Former Liberal Senator for South Australia

In this way, diversity targets should be set with meaning and have the right scaffolding to support them. They should be backed up with leadership accountability and approached with the same rigour and testing as any other business strategy.

Consider the following options, each found to be effective when looking at the programs and initiatives taken by organisations who have achieved balanced gender diversity in leadership:

- Flexible working arrangements. Supporting your workforce through life transitions. Family demands are an often-cited barrier to female advancement.

- Tailored pipelines for female middle management. Putting a focus on advancing talent (identify middle managers for promotion) and targeting the removal of barriers affecting these individuals.

- Blind resume screening. Removing any details that may increase the risk of an unconscious gender bias.

- Diversity taskforce. Create a team of diversity champions dedicated to finding and managing gender diversity programs best suited to your workplace.

- Quotas. While there is concern that quotas create negative attitudes toward those appointed to these roles, in the long run, they provide sustainable change by creating more female role models, which can profoundly shape the experiences of other employees within the organisation.

- Quantify progress. To find the best fit solution for women in your unique organisation, collect data to measure what workplace issues disproportionately affect female employees and assess the effectiveness of different solutions over time.

These commitments proactively change representation and set the tone for a more inclusive workplace.

3. Reinforce the systems

In order to truly break down barriers, we need to move past the bottom-line conceptualisation of value that women in leadership bring (i.e., financial performance) and consider the overall approach to retention, wellbeing and inclusiveness which have the potential to either support or undermine our efforts to improve diversity of any kind.

This requires significant work to strengthen our systems by building cultures that foster inclusion and belonging. Cultures that are characterised by transparency, fairness of opportunity, and are free from bias and discrimination.

In many ways, the ability to leverage diversity and draw on a variety of skills, perspectives and experiences yields great benefits for organisations. Yet so often our unconscious biases prevail, leaving executive and senior leadership roles dominated by the same narrow group. Fortunately, there are reliable and effective steps employers can take to break the bias. Only then will we achieve a true meritocracy.

Connect with us

If you would like to know more, please contact us here and one of our Workplace Strategists will be in touch within 24 hours.

References

Castilla, E. J., & Benard, S. (2010). The paradox of meritocracy in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(4), 543-676. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.4.543?casa_token=aloqdzkT_lIAAAAA:IZEwdDiwfLCRBX5FjqdhFmf3YT_XMBvU_emsiljAt59uda612sIoMRE2cgpOu669dH0jLIKa0HQi

Cermak, J., Howard, R., Ubaldi, N., & Jeeves, J. (2018). Women in leadership: Lessons from Australian companies leading the way. McKinsey Insights.

Dixon-Fyle, S., Dolan, K., Hunt, V., & Prince, S. (2020) Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters

McKinsey Insights.

Hoobler, J. M., Masterson, C. R., Nkomo, S. M., & Michel, E. J. (2018). The Business Case for Women Leaders: Meta-Analysis, Research Critique, and Path Forward. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2473–2499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316628643

Hoyt, C. L., & Murphy, S. E. (2016). Managing to clear the air: Stereotype threat, women, and leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 387-399.

Koch, A. J., D’Mello, S. D., & Sackett, P. R. (2015). A meta-analysis of gender stereotypes and bias in experimental simulations of employment decision making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 128.

Liveris, C. (2020) Gender Equality at Work 2020. Retrieved from: https://conradliveris.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/gender-equality-at-work-2020-excerpt-corporate-leadership.pdf

Madsen, S. R. (Ed.). (2017). Handbook of research on gender and leadership. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Perryman, A. A., Fernando, G. D., & Tripathy, A. (2016). Do gender differences persist? An examination of gender diversity on firm performance, risk, and executive compensation. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 579–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.05.013

Tate S. & Page D. (2018) Whiteliness and institutional racism: hiding behind (un)conscious bias, Ethics and Education, 13:1, 141-155, DOI: 10.1080/17449642.2018.1428718

Hill, C., Miller, K., Benson, K., & Handley, G. (2016). Barriers and Bias: The Status of Women in Leadership. American Association of University Women.

Kilian, C. M., Hukai, D., & McCarty, C. E. (2005). Building diversity in the pipeline to corporate leadership. Journal of Management Development.

Green, A, Alhadeff, M, Akhmetova, Z and Claire, T (2017) What’s Working to Drive Gender Diversity in Leadership, Boston Consulting Group (BCG), https://www.bcg.com/en-au/publications/2017/whats-working